VANISHING POINT at 50: And The Road Goes On Forever

The vanishing point on any image plane is where two lines appear to merge, or where something disappears altogether. It’s an optical illusion that also happens to be inherent to nature and our own existence. No where is it more apparent than in the expanse of the Southwest desert, where endless blue sky meets sun-baked clay on almost every horizon. It has inspired explorers, pioneers and those that seek elusive truths. One of those was Guillermo Cabrera Infante, who (under the pseudonym Guillermo Cain) wrote a screenplay partially based on a disgraced former cop and another man who refused to give up a high-speed police pursuit and died as a result. That screenplay was Vanishing Point.

Part gearhead favorite, part counterculture cult film, part existential meditation, Vanishing Point grew from an initially discarded Fox property to cherished road movie over the ensuing decades. It debuted in America on March 13, 1971 to middling reviews and a less-than-impressive box office, leading the studio to dump it after a few weeks. However, moviegoers in the UK and Europe - particularly the Soviet states - responded enthusiastically to the film, which in turn convinced Fox to bring it back as the “bottom” on a double feature with The French Connection. And from there it grew.

Kowalski (Barry Newman)

The plot: Kowalski is a car delivery driver, and he needs to get a new Challenger from Denver to ‘Frisco by Monday afternoon. He bets his buddy the cost of the speed he bums off of him he can make it there by 3PM Sunday. That’s it. What we learn of Kowalski is through various flashbacks and exposition from other characters. Decorated Vietnam vet, disgraced cop, failed motocross and race car driver. Kowalksi himself - embodied by relative unknown Barry Newman, in his second leading role - barely speaks throughout the film, letting his eyes and driving skills do most of the talking.

The entire movie could be seen as a flashback, as the opening scene foreshadows the finale. The roadblock is set, the townspeople gather and wait, and Kowalski speeds straight towards his destiny. He passes a black sedan in a freeze frame and disappears; the sedan moves on, driven by Kowalski 48 hours earlier. As director Richard Sarafian explains in the featurette Built For Speed, he sees the film as a Mobius strip, which ironically eliminates the concept of a vanishing point from the movie itself.

The longest time the film spends in any one place is the town of Chico, where it both begins and ends. DP John A. Alonzo, who would go on to critical acclaim with Chinatown and other stellar work, captures the dusty, hazy realism of small town Nevada, using townsfolk as extras and shooting them in their natural state. It gives the scenes a documentary feel, which is starkly juxtaposed to the rest of the movie and its existentialist, almost supernatural elements.

Kowalksi and the Prospector (Dean Jagger)

Much has been said about Vanishing Point and its symbolism relating to the death of the Sixties and subsequent birth of the nihilistic, paranoid Seventies. Those points are valid, but tend to overshadow the film’s spirituality and religious allegories. While it ostensibly rejects religion and its associated authoritarianism, our hero wanders the desert lost, silently ponders his existence, encounters a dangerous serpent, runs into an old man (Dean Jagger) that helps him on his journey, and witnesses a Pentecostal revivialist ceremony. He eventually leaves this all in his rearview, perhaps feeling out of place even with those that live on society’s fringe, but in doing so he crosses several other sets of tire tracks in the desert. Are they his? Has he been here before? And if so, was any of this real?

The strongest theme of spirituality and The Other comes from Super Soul, the boisterous, blind DJ played by Cleavon Little (Blazing Saddles) in his film debut. As Kowalski speeds through roadblocks and eludes “the big blue meanies” from Colorado to Utah to Nevada, Super Soul “sees” Kowalski with his mind’s eye, and eventually communicates with him through his broadcasts. Though they both gain enemies - the authorities that are pursuing Kowalski and those that decide to shut Super down in the movie’s most violent and disturbing scene - they share a purity of intent.

Super Soul (Cleavon Little)

Kowalski means no one harm, as evidenced by him stopping to check on various cops (and one speed freak in a Jaguar) that end up crashing when they go up against him. We see that he was kicked off the police force for not allowing a superior to sexually assault a teen girl. When the nude biker (Gilda Texter) offers herself to him in the movie’s most famous non-driving sequence - because a needle drop from Mountain’s “Mississippi Queen” set to an angelic, bronzed naked California girl riding a dirtbike in slow motion is cinema, goddamnit - he smiles, thanks her and politely declines.

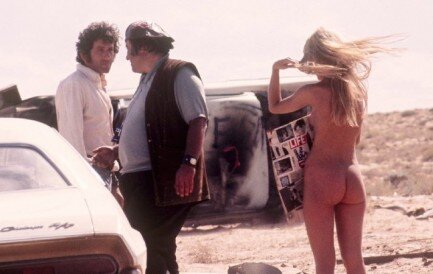

Newman, director Richard Sarafian and Gilda Texter behind the scenes

It’s no coincidence the biker bears a strong resemblance to Kowalksi’s girlfriend Vera (Victoria Medlin) who drowned in a surfing mishap years before. Perhaps she reminds him of better times, or that nothing gold can stay. But Sarafian, Newman, and other principals have all mentioned that even if Kowalski was unsure of what he was doing, he knew he just had to keep moving.

The biker’s boyfriend Angel (Timothy Scott) hooks Kowalski up with more speed before the final leg of his journey. Vanishing Point has a reputation as a “drug” movie - with its hippies, pill popping (one of the taglines for the movie is literally ‘thrills, spills and a handful of pills’) and general antiauthoritarian bent, that’s not necessarily wrong. But the Bennies are a means to an end. Kowalski simply needs to stay awake. That is, until he meets The Hitch-hiker (Charlotte Rampling) on his last night. This scene was cut for US audiences, supposedly because the powers that be didn’t think they would get it. While the dialogue in the scene is mostly vague and esoteric - “I’ve been waiting for you forever…everywhere, and forever…patiently. That’s the only way to wait for somebody” - it’s not impenetrable. She is the angel of Death, or as Sarafian puts it in the film commentary, “the hitchhiker represents inevitability”. Apparently Death has really good weed, because she rolls a giant joint and passes it to Kowalski before they make love. He wakes up the next morning to find her gone and sets out for San Francisco.

The end

The townsfolk gather, moths to flame, as Kowalski approaches the city limits. News trucks and squad cars surround the final stretch, and the atmosphere is more akin to a carnival or holiday parade. Even at this late point, if Kowalski gives himself up he’s not looking at a lot of jail time. Reckless driving, failure to yield, all the shit most fast drivers have been to court for at some point. But like every other turning point in Vanishing Point, it isn’t about the law or even the road. It’s about freedom and conviction. Going back to Built For Speed (filmed in 2008) you can hear superfan Chris Cornell talk - in a now-heartbreaking light - about relating to the film’s themes of isolation and disillusionment, and he’s right. Kowalksi isn’t connected to this town, to America, or anywhere else. The road just happens to be here, and he only exists to beat it. The last time we see Kowalski, he’s smiling, pedal to the metal, not because he knows he’s going to die, but because he believes he can make it. He’s just passing through this world, never really belonging to it, forever speeding towards that disappearing spot on the horizon just out of reach.

Setting up the final shot

As previously mentioned, Fox flushed Vanishing Point not long after it debuted. Like other films that were initially discarded in that era, it grew a fanbase over time through drive-in double bills and TV broadcasts. Sarafian had initially wanted Gene Hackman for the Kowalski role, but studio chief Daryl Zanuck insisted on Newman or else he would not finance it. Sarafian hints at Newman’s father being involved, and that he was close with Frank Sinatra and “attended some Italian funerals in New York”.

The budget was a modest $1.3M, with Sarafian going over by about $80K mostly due to the soundtrack. The incidental music cues were done by a bluegrass/Americana duo, while other notables were the first licensed recordings featuring Kim Carnes (“Betty Davis Eyes”) and Delaney & Bonnie and Friends, who played the band in the revival tent scene. The electrified country rock and blue-eyed soul complement the open vistas and endless highways that Sarafian and his small but dedicated crew capture. The film’s editing and music played a large part in making the driving scenes more compelling as well, since the “chase” the film is based on relies heavily on Kowalski and his Challenger alone in the desert.

Vanishing Point’s legend and popularity only grew. Primal Scream wrote what is basically an alternate soundtrack to the film in 1997, and before that Axl Rose recited Super Soul’s famous “last American hero” monologue at the end of “Breakdown” on Use Your Illusion II.

The most direct homage came in Quentin Tarantino’s half of Grindhouse - the second billing, coincidentally enough - where the women of Death Proof not only discuss Vanishing Point, but find a white 1970 Challenger and engage in a full-on full-contact chase with Stuntman Mike’s black ‘69 Charger (perhaps itself an homage to the chase scene from Bullitt).

As time inevitably moves forward, one’s relationship with a film can change with it. As a young man, few things sound as appealing as roaring through the Southwestern highways in one of the greatest muscle cars ever built, with seemingly no purpose, responsibility or agenda other than speed (and yes, maybe a nude dirtbiker or two). In later years, the moments in Vanishing Point that hit a little harder are Kowalski’s quietest moments. when the engine is idling or off and he’s alone with his thoughts. Between those beats and the flashbacks, we get a sense of what shaped him as a man, a driver, a human being. And while we’ll never know what exactly was going through his head - regret, grief, acceptance, anger, serenity - we can rest assured that he’s out there, burning down the blacktop, our soul hero in his soul mobile.